The Great AI Weirding

Or how AI will put you in recursive rat races if you let it, and you probably will.

✋ This post uses images, so if you read this on an email client, enable the “display images from sender” to get the most out of the post. If you are a new subscriber, welcome! If you find these writings valuable, consider sharing them with a colleague or giving a shoutout on Twitter. No generative tech was used in writing this article.

You know when you have some ideas brewing in your head, but you cannot immediately put them into words because the proper terminologies don’t exist, and you are so deep in the rabbit hole that anything you say comes out garbled, and it is too much work to climb out of the rabbit hole to give a guided tour. So you don’t bother saying it out loud, except maybe scribble something cryptic in your notebook? This experience is routine for me since much of my “thinking” happens without words.

However, today, I stumbled on two posts by people from different walks of life that force-crystalized everything together in a moment, like a supersaturated solution waiting for that alien particle to grow a giant crystal around it. I will highlight essential pieces from these posts to help me build what I am saying, but it is worth reading the linked posts in their entirety.

RL Career Games

The first is by Ben Recht, a well-known AI researcher, from his argmin substack (recommend subscribing), where he draws attention to the problem of “over productivity” in AI. Ben notes that typical faculty applicants these days at Cal, where he teaches, have 50 or so papers under their belt at elite venues like NeurIPS or ICML as compared to needing one good paper when he graduated.

I worry that overproductivity is an unfortunate artifact of “Frictionless Reproducibility.”Artificial intelligence advances by inventing games and gloating to goad others to play. I’ve talked about how benchmark competitions are the prime mover of AI progress. But what if AI people have decided (perhaps subconsciously) that publishing itself is a game? Well, then you can just run reinforcement learning on your research career.

Running RL on academia has become easier as tooling has improved. Writing LaTeX is so streamlined that every random conversation can immediately become an Overleaf project. Code can be git-pulled, modified, and effortlessly turned into a new repo. Everyone has a Google Scholar page highlighting citation counts, h-indices, and i10 numbers. These scores can be easily processed by the hiring managers at AI research labs. The conferences are all run by byzantine HR systems that accelerate form-filling and button-checking. And the conference program committees have all decided to have a fixed acceptance rate that is low enough to give an aura of “prestige,” even though the acceptance process is indistinguishable from coin flipping. They claim a conference has clout if it has a fixed 25% acceptance rate. If the community sends 100 papers, 25 are published. If it sends 10000 papers, 2500 are published. It doesn’t matter if they are good or not.

— Ben Recht, Too Much Information

These RL career games (my shortcut for “Running RL on academia”) that Ben talks about are not just at play in faculty jobs alone. We see this even in AI Ph.D. grad applications, where having at least one high-quality published paper has become an unstated requirement at many schools, and it is unsurprising to see students come in with multiple of these.

The second post I want to draw your attention to comes from someone I don’t know, and I have never read their writing before — Benedict Hsieh, a software engineer. I deeply resonated with his post titled “math team”. It felt deeply personal because I did competitive math as a teen, and now, my nephew in grade 8 is training for that. In Benedict’s post, Ben’s RL career games begin as early as college admissions (although some parents will swear it starts with getting your child into the right kindergartens). Benedict writes, on his college application journey:

It's terrible to contemplate, even now. Competitive math was just one piece of it. We started school at 8 and went until 4:30. Nights were for other worthless extracurriculars to pad out our applications. I did debate team and jazz piano, student journalism and improv, extra science and math classes on weekends. None of it meant anything. Each activity was like the last, one box ticked after the next, each school day starting when it was still dark out and only ending when it was dark again, every hour blended together into some kind of gray resume goo.

The worst part was knowing that it was all going to be extruded into a few lines in an application form, that a committee would review for about ninety seconds before moving onto the next perfectly interchangeable application from some other straight-A tryhard.

— Benedict Hsieh, “math team”

Sounds familiar? Looks like these crazy RL career games that take hold during teen years go on until tenure and, for some, beyond that.

Not Just Academics

These games are not just for the academics. Many AI industry labs have thresholds on H-Index for hiring, and your CV can get a desk reject because of it. Some sophisticated HR folks I worked with have unsophicatedly used publication counts and recency to filter the sea of applicants, even for the run-of-the-mill ML engineering research jobs. This unbridled productivity is not just in publishing papers. Today, your GitHub bathroom wall, your Kaggle ranking, and your Hugging Face leaderboard appearances can determine whether your resume will head to the bin or the hiring manager’s inbox.

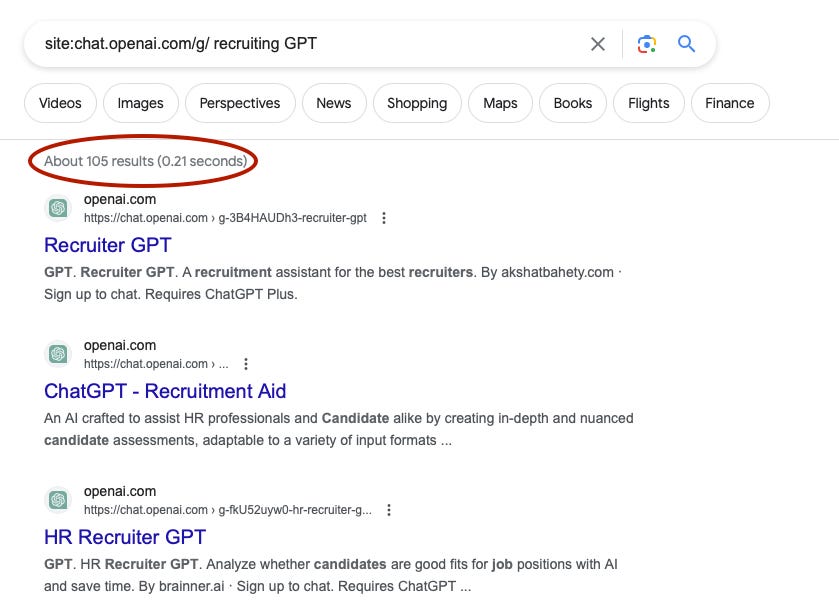

Some startups have now taken it upon themselves to codify these terrible metrics into HR products. A simple Google search will reveal over 100 “custom GPTs” incorporating such ideas using OpenAI’s new GPT marketplace, in addition to the full-blown HR products I mentioned earlier.

We cannot blame entrepreneurs or the recruiters in the trenches for this. Entrepreneurs will build, and HR folks, like all knowledge workers, will take refuge in AI. It doesn’t matter if you agree with it, but this is how things seem to be headed. All you need is your email for these products to entity-link you with your socials, GitHub, Kaggle, and HuggingFace accounts.

The Price for Legibility

However, there is a massive human cost to all of this. We, collectively as a community, are forced to play these stupid RL career games because if you refuse, you become illegible and, consequently, invisible to sources of physical, emotional, and intellectual sustenance. It’s like we are all trapped in vicious cycles of RL career games while hoovering up others in these cycles.

Once a critical threshold of people start playing these RL career games, these terrible metrics get elevated to some weird group fairness metrics for hiring/admissions/compensation decisions, no matter how inequitable these games are and how disparate the outcomes are. The metric has moved beyond convenience to something hard to root out. The terrible metric becomes tyrannical, and complaining about it makes you sound like someone who “blames the game for being a bad player”. Even if it was a game you never wanted to play, to begin with.

Suppose you think, okay, fine. If bean counters love metrics, and RL cycles and metrics are unavoidable, why not invent better metrics? How about we replace the H-index with something else with different fairness guarantees? If you do that, you will live long enough to get crushed by it in the career RL loop and see it find a spot in Goodhart’s Graveyard. In any case, a purely opt-in metric that’s inclusive of people who decide not to play the RL career games seems impossible.

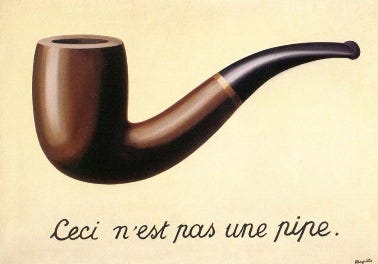

Ceci n'est pas une pipe

Intrinsically, a well-designed metric is neither terrible nor tyrannical. At a deeper level, something else is going on altogether that’s changing the nature of things themselves and, hence, our perception of these metrics. For example, in AI, a paper has stopped being a paper. A model has stopped being a model. A dataset, a dataset. A repo is not just a repo. All of these things have gone beyond what they point to.

I am old enough to remember holding a hardcopy NIPS (as NeurIPS was called back then) conference proceedings reverently in my hand. Every paper in it meant a piece of knowledge, like a tiny grain of sand that gets washed up to define the shoreline. An AI paper then was just a paper. Today, an AI paper has mainly become an instrument to get a job interview, raise, bonus, school admission, or startup funding. Secondary gains have become primary. With frictionless reproducibility, anyone can git clone, make small changes, re-run the experiment script, and publish a new paper or a model to accrue whatever gains these artifacts point to. This goes for publishing AI models, too. It used to be that publishing models were thankless work, but once AI model releases started getting attention on social media like product releases, your average hackers now have a field day hacking into that fame. The recipe is something like 1) taking an existing model, 2) taking an existing dataset, 3) finetuning the model with the dataset for 1-2 epochs using an existing finetuning script, and 4) uploading the model to HuggingFace to secure a place on the leaderboard and whatever signaling that comes of it.

All of these are fine in isolation, and my argument is not that we have less software engineering around experiments and add friction to reproducibility. All of this is inevitable, but we should also be aware of the social dynamics in which this lands AI researchers.

Who is an AI Researcher

When a paper, model, repo, and dataset become more than what they mean today, one might wonder, what has happened to the “AI researcher”? Before I dive deeper into this, I want to recall the “math team” post again, specifically:

A quick aside on terms here. A mathematician seeks the patterns that unify all things, that allow systems of dizzying complexity to grow from just a few elegant formulas. For example, consider the exponential function f(x) = aex. It's the function that equals its own derivative – that is, the rate of change of the function is the same as the function itself. In this compact equation we see the skyrocketing population of rabbits on a fresh island, or the arc of a stone falling to earth, or the beams of radiation spitting out from a plutonium core. Architecture, biology, economics, music theory, astrophysics, a dozen other fields all bottom out somewhere in math. A mathematician's motivation might be just as selfish as anyone else's – fame, curiosity, just knocking a chip off their shoulder – but their goal is almost definitionally pure. I was not a mathematician.

A mathlete is someone who participates in math competitions. He (almost always he) uses the elegant axioms of mathematics, the underlying structure of creation, in the same way that a drunken barfly uses a grip of darts, flinging them against a wall to impress friends or strangers. The patterns they leave mean nothing at all, except that sometimes they land in this curvy bucket instead of that one, scoring five points, or a hundred. The only point is to win. On math team, we were mathletes.

— Benjamin Hsieh, “math team”

To ask who is an “AI Researcher,” “Research Scientist,” or any paraphrase of these titles is no longer considered PC. Most people (including HR) will call anyone with an AI jargon word cloud hovering over them an “AI researcher”. So, we now have one bucket for anyone with “AI researcher”, and fairness demands we impose the same metrics on people in the same bucket. So, if you want to spend time genuinely studying or understanding something (what “research” meant once), you will be dinged for whatever metrics people use for “AI researchers” these days — number of model releases? their download count? H-index of your paper mill? git commit frequency?

Leaderboard Inversion

My first experience with how working in AI influenced how I worked was at CoNLL shared tasks. Before Kaggle, academia and organizations like NIST pioneered leaderboards using multi-decade-long shared tasks at workshops like CoNLL, TAC, and ILSVRC. Leaderboards are great, and many have written about how leaderboards can be a catalyst for progress on a focused topic. With Kaggle, like Topcoder before it, two new things happened:

The first was scale. Leaderboards no longer represented a small group of people working (semi)anonymously on a niche problem close to their research interests. We now have large swaths of people whom decision-makers can compare against each other over AI problems that have little bearing on their personal interests.

The next is what I call Leaderboard Inversion. With a single group-by-aggregate query, Kaggle turned users’ ranking on individual projects into a ranking of the users themselves. I may have mindlessly clicked “Accept” on the ToS of the site, but did I want this? Or did I foresee how this ranking would be used against me by people I would never see or know if I did not play Kaggle’s silly RL career games? Absolutely no.

Harry and the Recursive Rat Race

In “math team”, Benjamin provides Harry, an archetype for people who try not getting sucked into career RL games.

Of the dozen serious competitors in my grade, I think only two had any specific interest in math. One of them was actually so interested in math that he became useless at competitions and eventually stopped showing up to practice. Harry wanted to learn new theorems and theories, not spend his time combining old ones in arbitrary and nonsensical ways. He was a mathematician, not a mathlete.

…

I ran into Harry at a party a few years ago. He studies as much math as he can, taking programming jobs when funds start to run low. I couldn't really follow the work that he tried to explain to me, something about counting the paths in a changing topology. What would that be like, I wondered, as his words floated gently through the space above my head, to just be interested in something, not as a stepping stone or as a resume line, but just to sit down and count the paths, just because you wanted to know how many there were?

— Benjamin Hsieh, “math team”

If you are a Harry, don’t identify as a Kagglete, and have little interest in playing others’ career RL games, life can get quite challenging, especially as you take on more adult responsibilities. While rat races existed at all times, this extreme quantification and tracking, and RL games imposed on them, allows everything to be turned into a rat race, so much so that the moment you step out of one, you are on a different treadmill running a different rat race — a recursive rat race!

The Great AI Weirding

What’s happening in the AI research world is a small microcosm of the greater AI Weirding of society. We saw examples of simple quantification of people and activities, such as using counts of likes, stars, commits, and papers, and even more informed metrics like H-Index can lead to strange outcomes. AI will make the world even more quantifiable and, in many cases, falsely quantifiable. Ever since the first ape held two sticks in the left hand and three in the right and wondered which was more, ranking things by quantity is in our nature. The ape’s descendants have now discovered a ranking hammer, and everything will look like ordered lists. Ordered lists bring legibility, and what is not legible cannot be governed and subject to value extraction. The false quantification and rank ordering of things using AI will bring real-world weirdness in how people function, which has nothing to do with the functions they carry out. I call this the “Great AI Weirding”. “Weirding” is the process by which something becomes weird. It was first coined by Hunter Lovins, the founder of Rocky Mountain Institute, in the context of climate change, extended by Thomas Friedman in the context of globalization (“global weirding), and others, including Venkatesh Rao, most notably, in the context of social media.

If you are familiar with machine learning, you know that you don’t need interpretable metrics or even any kind of quantification to rank order things. And that’s the scary part of all this. Once you rank order outputs, you can rank order the people behind the outputs without their consent by leaderboard inversion and use that to make opaque decisions for them and send them desk rejections for things that matter, like jobs, promotions, and funding, imposing the fear of the metric. Unlike national credit scores, these shoddy metrics will be unregulated, and even the existence/involvement of a metric or a scoring tool will not made public.

There is a lot more I want to say about the Great AI Weirding, but this post is already becoming too long, and I want to keep it focused on one aspect of how AI is weirding the future of work and workers. More later.

Postscript: I want to offer my sincere gratitude to the paid subscribers on this platform and elsewhere, who help me, even if in small ways, to escape the RL career games and be a Harry of AI. Knowledge should be freely accessible, and I will not paywall any of this content. I appreciate you becoming a paid subscriber if you are not already. Happy Holidays!

Hi Delip, There is so much here that I resonate with. These forces you are highlighting speak to a broader malady that will be our undoing if the tide does not turn. That is disconnection. Disconnection from ourselves, from each other, and from nature. It reminds me of an event I participated in a number of years ago now in the Valley on AI. In the first group discussion, the discussion lead asked "how do we accelerate our progress toward the singularity?" I about jumped out of my chair, shooting my hand up to interject with "I object to the premise of the question!" The techno-optimism on display back then was shocking to me, as two weeks before then I had been sitting with a single mom with 10 kids on the south side of Chicago to better understand her day-to-day struggles. The folks in that AI gathering might as well have been living on another planet. I know we've seen nothing yet in terms of the weirding to come. And I pray we come to our senses and change course before it's too late to overcome the ecological disasters that are well underway.

> You know when you have some ideas brewing in your head, but you cannot immediately put them into words because the proper terminologies don’t exist, and you are so deep in the rabbit hole that anything you say comes out garbled, and it is too much work to climb out of the rabbit hole to give a guided tour. So you don’t bother saying it out loud, except maybe scribble something cryptic in your notebook?

This is so familiar to me, but I've never seen someone describe it so well. My PhD was basically from slightly before ELMo until now, so I feel like I understand the arc of development pretty well. I end up at a loss for words trying to communicate my mental model to others. It comes up often with AI doomer types. Bridging the gulf between our perspectives would require so much tacit knowledge, I can't imagine doing it successfully. Or maybe I'm the crazy one and all my hard to verbalize thoughts are incoherent.