Understanding NIH’s 15% Overhead Cap

How this little publicized news will change science, healthcare, and universities. This is not an AI post, but more important than anything that's going on in AI.

Every 3 weeks, I get a highly-specialized treatment for a rare disease. The innovations behind that treatment were made possible by multiple National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants. I worked on a healthcare startup for evidence-based medicine based on PubMed. Most of what’s on PubMed, and what doctors rely on to offer all of us the best healthcare, is made possible by NIH grants. At Penn, where I am affiliated, there are people who are inventing life-saving work regularly, including people who have brought home nine Nobel prizes in medicine. All of that is made possible by the NIH. The NIH is one organization that touches every American whether they know it or not.

Today, the Trump administration announced a new standardized 15% indirect cost rate for all NIH grants (NOT-OD-25-068). This seemingly technical change will devastate American medical research and US healthcare in one stroke.

Understanding Indirect Costs

In university administration parlance, indirect costs (also called Facilities & Administrative or F&A costs) are the overhead expenses of research – everything from laboratory maintenance and utilities to administrative support and compliance oversight. These aren't luxuries; they're the essential infrastructure that makes research possible.

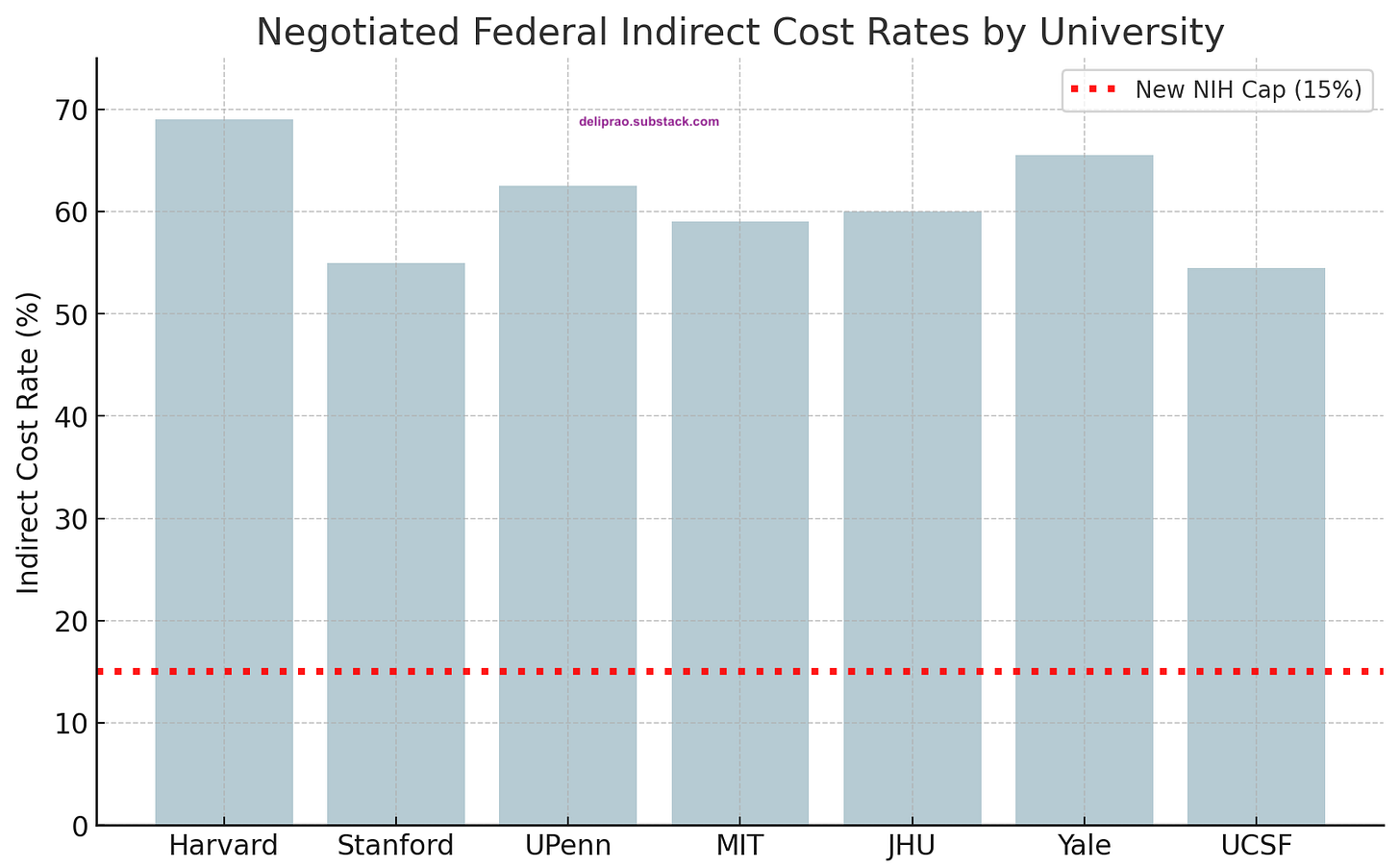

Historically, NIH honored individually negotiated rates with universities, which averaged 27-28% of total grant costs. In fiscal year 2023, this amounted to about $9 billion of NIH's $35 billion budget. The rates varied significantly among research institutions, reflecting their different infrastructures and costs. Harvard's rate stood at 69%, while Yale commanded 67%. The University of Pennsylvania operated at 62.5%, MIT at 59%, and Stanford at 55%. Even the University of California campuses, with their state support, required rates between 52% and 55% to maintain their research operations.

While NIH argues this change aligns with private-sector norms (many foundations pay 0-15% overhead, e.g. the Gates Foundation allows 10% for universities), it misses the point that universities were able to offer that subsidy to private corporations because the federal government, indirectly, picked up the slack. The stark reality is most universities have never operated their NIH-funded projects on such a lean overhead allowance.

To get an idea of how drastic the cuts are, here’s a look at what some top institutions have been charging in recent years, compared to the new 15% cap.

Quantifying this Financial Earthquake

The magnitude of this change becomes clear when examining a typical $1,000,000 grant for direct research costs. Under previous rates, Harvard would receive $690,000 in overhead, Stanford $550,000, Penn $625,000, and MIT $590,000. The new 15% cap slashes these amounts uniformly to $150,000 – a devastating reduction of 75% or more in indirect funding. Even institutions with more modest rates around 50% will watch their overhead funds shrink by two-thirds.

The system-wide impact staggers the imagination. Of the approximately $9 billion NIH spent on indirect costs last year, only about $4-5 billion would have been paid under the 15% rule. This creates a $4 billion shortfall that must be absorbed by research institutions already operating on tight margins.

Institution-by-Institution Impact

For research-intensive universities, the dollars at stake are eye-popping. Consider that NIH spent about $9 billion on indirect costs last year. If the 15% rule had been in place, only ~$4–5 billion would have been paid out for overhead (rough estimate), meaning roughly $4 billion less flowing to universities’ research operations. That money now either stays in NIH’s budget for other uses or funds more direct research – but it leaves a gaping hole in university finances.

Let’s look at potential losses at the institutional level:

Harvard (which received around $270M in NIH awards for its medical school alone in one recent year) would see overhead funding on those awards drop from ~$186 million (at 69%) to ~$40 million at 15% – a loss of over $140 million on that portion of its NIH portfolio.

Johns Hopkins University, the top NIH-funded university with ~$843M total NIH funding in FY2023, likely had on the order of $300+ million in indirect cost recovery. Under a 15% cap, JHU would get only ~$100 million, leaving a $200+ million annual deficit to cover for its research infrastructure.

MIT leaders estimated that a harsher 10% cap (floated in an earlier proposal) would cost MIT about $100 million per year in lost research cost reimbursement. A 15% cap isn’t as extreme but would still cost tens of millions annually. MIT’s Provost Martin A. Schmidt, and VP for Research Maria T. Zuber noted that losing $100M/year is akin to the blow MIT took in the 2008 financial crisis – except this loss would be permanent, not a one-time dip. Recovering $100M in perpetuity would require an extra ~$2 billion in endowment, they calculated. Few schools have that kind of spare capacity.

University of Pennsylvania (with ~$500M/year in NIH funding in recent rankings) at 62.5% overhead would have expected around $190M in indirect cost recovery. Under the new policy, for the same direct funding, it would get only ~$75M, losing on the order of $115 million that previously helped pay staff and utility bills.

Other large R1 universities like Stanford, University of Michigan, Yale, UCLA, etc., each stand to lose on the order of $50–$150M or more annually in overhead funding, proportional to their NIH grant volume and prior rate. As Carl Bergstrom summed up, for a big research university this policy creates a “sudden and catastrophic shortfall of hundreds of millions of dollars against already-budgeted funds”.

These losses aren’t abstract – they blow a hole in university research budgets effective immediately. NIH’s notice makes the 15% rate apply to current grants moving forward, not just future awards. Universities had budgeted their multi-year grants assuming (for example) a 60% overhead rate for the duration; now, overnight, they will only receive 15%.

Research universities typically pool their indirect cost recoveries into central funds that pay for facilities operations, research support offices, regulatory compliance (IRBs, animal care, radiation safety), graduate student services, IT infrastructure, libraries, etc. With a sudden 75% cut in the largest source of funding for those activities, university finance offices are looking at immediate budget deficits. Many schools will have to revise their budgets this fiscal year to absorb the hit. As one commentator on r/Professors bluntly put it, “This [overhead revenue] is THE business model of R1 universities. This is going to be a disaster”.

University CFOs and finance directors are likely doing triage calculations right now. Institutions that relied heavily on NIH overhead to balance their books may even face credit rating concerns or cash flow issues. Unlike a business that can quickly trim product lines, universities have ongoing obligations: buildings that must be kept open, staff on payroll, multi-year research commitments, and compliance mandates that can’t be ignored. So how will they adjust? The options are all painful.

Institutional Response Options

Facing such a steep drop in funding, universities will need to find money elsewhere or cut costs (or both) to keep their research enterprise running. Some likely implications and responses being discussed across campuses:

Tapping Other Funding Sources: Universities may dip into endowments or reserves to temporarily support critical research infrastructure. Wealthy institutions might reallocate endowment payout to cover what grants no longer do. However, as MIT’s leadership noted, compensating even a $100M shortfall would require billions in new endowment – not a sustainable solution. Less wealthy universities simply don’t have large reserves to offset a loss of this magnitude.

Internal Budget Cuts: Expect belt-tightening across research support operations. Universities will likely freeze hiring for administrative and support roles paid by overhead. Some may institute layoffs among staff who facilitate research (grant administrators, technicians, facility managers) to reduce expenses. Non-essential programs or upgrades might be put on hold. In an internal memo, MIT warned it would need to “cut other expenditures (e.g., through layoffs, salary freezes, etc.), reduce the use of research facilities to cut operating costs, and/or allow facilities to deteriorate” if an overhead cap were imposed. These are no longer hypothetical measures – they are on the table now.

Limiting Research Volume: In a scenario unthinkable until now, some universities might accept fewer grants or curtail research projects. If every NIH grant comes with a built-in financial loss (because the 15% overhead doesn’t fully cover actual fixed costs), universities may become selective about what they can afford to subsidize. The MIT administration frankly stated that without sufficient indirect funds, they would need to limit the number of federal grants the Institute accepts. This runs counter to the mission of expanding research, but it may be necessary to avoid bankrupting the institution.

Shifting Costs to Grants (Direct Costs): Universities and faculty will obviously get creative in charging what they can directly to grants. We may see more budget line items for things that used to be covered by overhead – for instance, core facility fees, data storage, or administrative personnel now being listed as direct costs on grant proposals. However, NIH rules (and federal cost principles) prohibit shifting basic facilities and administrative costs to direct expenses in most cases. A PI can’t simply charge the grant for lab electricity or building depreciation – those are unallowable as direct costs. Some commenters speculate grant seekers will try to include more “support staff salaries, tool/equipment operating costs, etc.” in grant budgets to make up for lost central support. But the DOGE-y NIH may scrutinize such budget moves, and there’s a zero-sum problem: if every grant’s direct budget swells to include quasi-overhead items, fewer grants will be funded overall (since the total NIH budget is still finite).

Higher Tuition or Reallocating Teaching Funds: University finance officers might look to student tuition and general funds to subsidize research infrastructure that grants no longer fully support. This is a politically fraught option – essentially using education dollars or hospital revenue to underwrite research. But faced with keeping the lights on in research labs, some institutions might divert funds that would have gone to other areas. In other words, the shortfall might eventually be passed to students through higher tuition or fees, or by cutting other academic services to free up money for research support. (Public universities might appeal to state governments for help as well.)

Delayed or Cancelled Infrastructure Projects: Plans for new research buildings, major lab renovations, or facility upgrades could be put on hold. Those capital projects often rely in part on the steady stream of overhead recovery to justify the investment (or to pay debt service on bonds). With overhead revenues collapsing, universities may hit pause on expanding research space, which in turn limits growth opportunities for research programs. Maintenance budgets for existing labs could also shrink, risking a gradual deterioration of research infrastructure.

Emergency Advocacy and Policy Pushback: I suspect that universities are not going to take this lying down. Expect intense lobbying and negotiations to modify or reverse this policy. University associations (like the AAU, APLU, COGR) are likely mobilizing to demonstrate the damage such a cap will do to the national research enterprise. In the past, when a 10% NIH overhead cap was proposed, Congress showed little interest in adopting it. Research advocates argued that cutting indirect cost support is effectively cutting research itself, because universities will be forced to scale back. We may see legal challenges or legislative action if universities claim NIH exceeded its authority (NIH did cite federal regulations allowing it to deviate from negotiated rates, but such a sweeping change may yet be tested). At minimum, university leaders will be very vocal about the devastating effects this will have if not rethought.

Impact on Clinical Trials and HealthCare Broadly

The cap’s impact will be particularly acute for clinical research and trials at institutions that previously received 50–60% indirect cost rates. These NIH-funded clinical trials often take place in teaching hospitals with significant infrastructure costs – e.g. nursing support, imaging, pharmacy, data management – that were partly covered by a robust F&A rate. Under a 15% cap, the overhead reimbursement on a given trial grant plummets. For example, on a $1 million direct-cost clinical trial, an institution with a 60% rate used to receive ~$600,000 for indirect costs; now it would receive only $150,000. That $450,000 shortfall must be absorbed or cut. Hospitals may find it financially unsustainable to conduct some NIH trials unless they divert funds from elsewhere.

Institutions may scale back participation in NIH-funded trials as a result. Trials in areas like pediatrics, rare diseases, or public health – which are scientifically important but not big money-makers – could be hardest hit. In the past, major teaching hospitals accepted that NIH overhead wouldn’t fully cover costs, because it furthered their research mission. Now, with an even larger gap, they might prioritize industry-sponsored trials (which often pay higher overhead or per-patient fees) over NIH studies. This shift could reduce the number of investigator-initiated or public health trials, slowing clinical research progress in critical areas.

Then there is impact on clinical mission in academic medical centers (AMCs) where many advanced or experimental treatments are offered; if these hospitals face financial strain, it could affect the availability or cost of specialized care. In extreme scenarios, an AMC under budget duress might cut back on charity care or community health programs to save money, affecting healthcare access. There is also concern that financial instability in major teaching hospitals could drive consolidation or even closures, which reduces competition and often leads to higher local healthcare prices.

The False Economy

When a 10% cap was proposed in 2017, MIT's provost called it "an even graver danger" than direct budget cuts. As Carl Bergstrom noted, this creates a "sudden and catastrophic shortfall of hundreds of millions of dollars against already-budgeted funds."

While NIH argues this change aligns with private-sector practices, where foundations typically pay 0-15% overhead, this comparison ignores a crucial reality: universities could only offer those lower rates because federal funding covered the true costs of research infrastructure. Harvard's rate evolution from approximately 15% in the 1950s to nearly 70% today reflects not institutional greed, but the growing complexity and cost of modern research.

Long-term Consequences

The consequences of this policy extend far beyond university budgets. America faces an accelerating brain drain as researchers leave academia for better-supported positions elsewhere. Our global scientific competitiveness will decline as research institutions struggle to maintain their facilities and support their scientists. The development of new treatments and cures will slow. Hospital consolidation will increase, driving up healthcare costs. Research on rare diseases and public health challenges will suffer disproportionately.

Every treatment breakthrough, every new drug, every advance in patient care relies on the research infrastructure we've built over decades. By dismantling this system in the name of efficiency, we risk crippling America's capacity for medical innovation at precisely the moment when global competition in biomedical research is intensifying. The cost of this policy, measured in delayed treatments and lost opportunities for medical breakthroughs, will far exceed any short-term savings. We, our children, and grandchildren will pay the price for this short-sighted decision – unless we act now to speak up against it.

The taxpayer is represented by DFAS, which negotiates the indirect costs and has every incentive to negotiate a lower percentage because the money saved accrues to the overall NIH mandate, which is to support as much peer reviewed health related research as possible within congressional appropriations. Your unwarranted cynicism, demonstrated by no data or reference to fiscal abuse regarding the "NIH person" is a sad commentary on our current culture and exemplary of the forces that will cripple medical research if this mandate is allowed to proceed. Increasing government efficiency is a call that all can support but it is not likely to be achieved by a small group of uninformed 19-20 year olds calling for whole scale elimination of agencies or Draconian budget cuts.

The US Fed Govt spends $6.75T a year. The NIH's entire budget is $48B. This directive will massively hurt all universities (not just well-endowed ones), research institutions, and push back medical and scientific research decades to save what, $4B at most. That's <0.1% of the entire budget. This has nothing to do with living beyond our means. This is like giving away your kidney for a tootsie pop roll.